Earlier this year I was invited to do a Q&A with fellow historical novelist and Norman Conquest enthusiast Joanna Courtney over on her website, about the highs and lows of the writer’s life, the significance of 1066 and the appeal of historical fiction.

This week, to coincide with the publication

Earlier this year I was invited to do a Q&A with fellow historical novelist and Norman Conquest enthusiast Joanna Courtney over on her website, about the highs and lows of the writer’s life, the significance of 1066 and the appeal of historical fiction.

Earlier this year I was invited to do a Q&A with fellow historical novelist and Norman Conquest enthusiast Joanna Courtney over on her website, about the highs and lows of the writer’s life, the significance of 1066 and the appeal of historical fiction.

This week, to coincide with the publication of her latest novel, The Conqueror’s Queen, I’m delighted to return the favour, and Joanna has kindly written a guest blog post on seeing the events of the Conquest from a Norman perspective.

Joanna says:

“Ever since I sat up in my cot with a book, I’ve wanted to be a writer. I started out with short stories and have had over 200 stories and serials published in women’s magazines, but I always wanted to make it as a novelist. I was delighted, therefore, when PanMacmillan bought my historical trilogy, The Queens of the Conquest, telling the stories of the too-long-neglected women of 1066. The Chosen Queen and The Constant Queen are both out in the world and it’s always my great joy to hear from readers who’ve enjoyed them, so I’m over the moon that The Conqueror’s Queen is just about to join them. I really hope people like the Norman side of the story and watch this space for more queens in the future…”

The girlie side of the Normans: or, understanding Duke William

Joanna Courtney

The Normans don’t get a great press in history. They generally go down as Vikings without the sex appeal – dour, straight-laced, humourless warriors who liked to go about nicking other people’s countries. Here in the UK they do particularly badly because of the terrible ‘Harrowing of the North’ after the Conquest in which thousands of men, women and children were wiped out in one of the greatest acts of genocide in known history. The Normans’ reputation is perhaps, then, fair…

But is it?

My novel The Conqueror’s Queen is the third in my series The Queens of the Conquest about the wives of the men fighting to be King of England in 1066. When writing the first two books from the Saxon and Viking perspectives I happily embraced the idea of the Normans as the ‘baddies’. When I came to write from their point of view, however, I had to talk myself into looking at things from the other side of the story – which is always an interesting place to be. And so it proved.

I write from a female perspective and am therefore focused on domestic intrigue, human motivation, and political twists and turns, rather than the flesh and blood of the battlefield. I am not suggesting that the women back then (or now) were necessarily less ruthless or vicious than their male counterparts – indeed there is a fabulous woman called Mabel de Bellême whose reputation as a heartless poisoner proves this instantly wrong – but simply that women operated on their estates and at court, rather than with a sword in their hands. What I wanted to research therefore was why the Normans acted in such apparently dark ways. And there are many very sound reasons.

Normandy was a fairly new province in the mid-eleventh century, being only a little over a hundred years old. William was only the seventh duke and was still having to fight to establish and confirm his borders. Plus, William became duke aged only seven when his charismatic father died on pilgrimage. As a child and a bastard-born one at that, his rule was not readily accepted. There were plenty of cousins apparently concerned for the duchy in his control and – more to the point – keen to assert their own claim in his place. As a result there were endless rebellions throughout his early years of rule and stone walls (something Normans became famous for when they introduced castles to England) grew higher.

Inevitably in this warlike climate, the more cultural and domestic sides of life seem to have been neglected. When Mathilda of Flanders arrived to marry William in 1050 I suspect she did not find a place that was terribly congenial for women, especially in contrast to the far more peaceful and sophisticated court she’d grown up in, in Bruges. Mathilda and William’s long reign, however, changed all that.

William successfully put down all rebellions and gradually stability became the norm in Normandy. As a result the ducal pair were able to spearhead a huge programme of church-building which included their own beautiful Abbey aux Hommes and Abbey aux Dames in Caen. From this grand starting point they built Caen up into a hugely prosperous city and they also developed already flourishing Rouen. Bayeux, too, became rich and beautiful under the patronage of William’s extravagant half-brother Bishop Odo and it is safe to say that in the fourteen years between Mathilda marrying William and the invasion of England, Normandy was transformed into a far more stable, prosperous and elegant duchy than it had been before. It was this stability that enabled them, in 1066, to turn their eyes over the narrow sea…

Was William wrong to invade? He did not believe so and the more I researched his story the more I began to see it from his point of view. He was promised the throne by King Edward in Christmas 1051 when the Godwinsons (Harold’s family) were in exile. Most people, King Edward included, may have conveniently forgotten about that promise when the Godwinsons came back into power at court but William never did. It was why, when Harold visited Normandy in 1064, he forced him to swear an oath to uphold him as the next king.

William and Mathilda genuinely believed the English throne was William’s right and he wasn’t alone. When Harold was ‘treacherously’ declared king in January 1066 William sent straight to the Pope to denounce Harold’s reign – and the Pope did so. The Normans marched on England beneath a papal banner offering full benediction for their cause and whilst that may have been a handy political tool, it was also an unequivocal statement of William’s right to invade from the highest Godly authority on earth. It helped him attract soldiers from all over Northern Europe and undoubtedly shored up his own belief in his cause. God, in William’s eyes, wanted William to win – and God made sure that he did. We might sneer at that now but back then it was a very serious matter.

William, I believe, was a hard man but a straightforward and perhaps surprisingly loving one – at least in private. Of the three men fighting to be king of England in 1066 he was the only one who was faithful to his wife. A great man was more or less expected to have mistresses in those times but William never did. This may have been as a result of his Bastardy taint or may just have been his own love for Mathilda but it was remarkable enough for contemporaries to comment on it.

He was also very devoted to his mother, Herleva, and persistently promoted her ‘lowly’ family to high office. He was a man who prized loyalty, who worked hard to surround himself with faithful servants, and who rewarded them well for their devotion. He was not, perhaps, a lovable man, but looking at the 1066 story from his side enabled me to see that he was an earnest one who was driven by duty and a genuine desire to create a better world for his subjects.

And that is what he wanted for England too – but England would not play ball. The Harrowing of the North was a truly terrible act but when you look at it through the eyes of a man who had longed to be king for many years, who was desperate to be a good one, and who had spent his youth fighting off endless rebellions by people who wouldn’t trust him to do his job, it can perhaps been seen less as a cruel act than as a desperate one.

Call me girlie if you wish, but I firmly believe that all William wanted to do was be a good king. It is perhaps as much his tragedy as ours that history didn’t quite work out that way.

For more information about Joanna and her work, you can visit her website (www.joannacourtney.com) or her Amazon author page, and also follow her on Facebook, Twitter or Goodreads

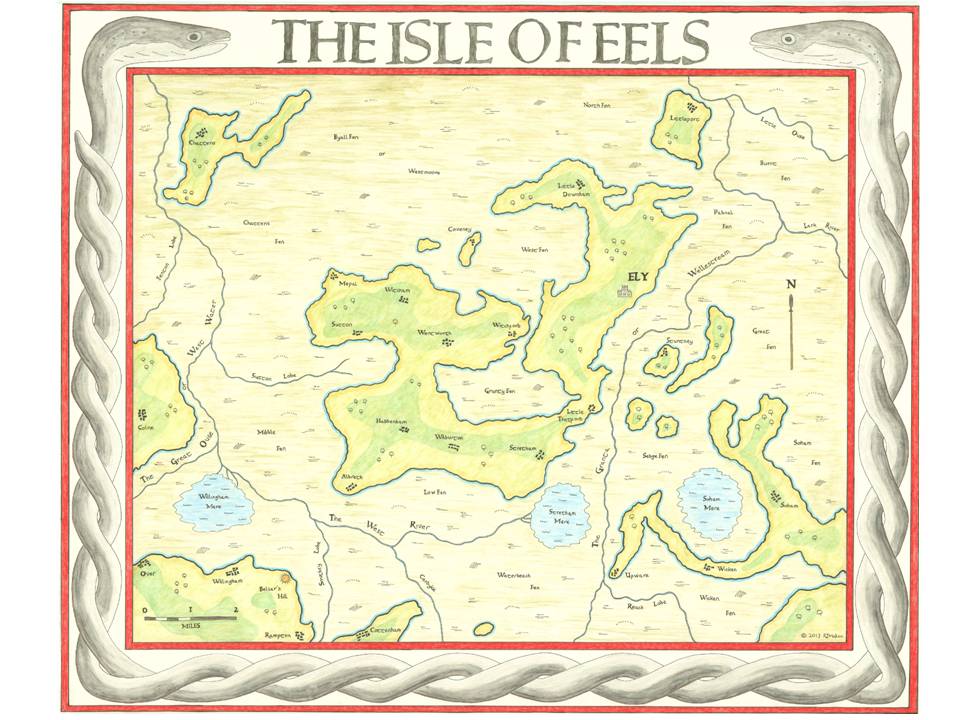

This week I’m pleased to be interviewing author and artist Rus Madon, the creator of the Isle of Eels map (below). The map reconstructs the historical geography of the Fens around Ely as they would have appeared at the time of the Norman Conquest: specifically in 1071, when Hereward the Wake and other rebels used

This week I’m pleased to be interviewing author and artist Rus Madon, the creator of the Isle of Eels map (below). The map reconstructs the historical geography of the Fens around Ely as they would have appeared at the time of the Norman Conquest: specifically in 1071, when Hereward the Wake and other rebels used the Isle as a base from which to conduct their guerilla war against the invaders.

Rus recently sent me a copy of his meticulously researched map, a remarkable piece of work and a wonderful resource for anyone fascinated, as I am, by the Fens and the role that they played in the years that followed 1066.

His work was also featured recently on the British Library’s blog. You can find him on Twitter at @RusMadon.

*

What was the initial inspiration for researching and creating the map, and how long did it take you to complete?

I am writing a Young Adult story about a girl who lives in modern-day Ely. She travels back in time to the year 1071 when Ely was defended against the Normans by Hereward the Wake. The more I wrote about 11th-century Ely, the more I wondered what it actually looked like. I knew that Ely had been an island, and I was having difficulty tracking where my characters were in relation to the original fens. So to help answer the question, I set about drawing a map of medieval Ely.

Including doing all the research, it took 200 hours to complete the map over an 8 month period in 2013. The original map is 1m x 1.2m and I had to make a workspace in the loft for all the materials, as it was too big to work on in the house!

Was this the first time you’d tackled a project like this?

The proper answer is yes. I do not have an artistic bone in my body, and made several attempts before ending up with the version you see. The eels in the border were particularly challenging (or should I say slippery!).

However, when I was a teenager in the mid 1970s, I spent an entire summer holiday recreating the map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings. By coincidence, that is also 1m x 1.2m, and was drawn on a big piece of butcher’s paper! It hangs on the wall next to my map of Ely.

However, when I was a teenager in the mid 1970s, I spent an entire summer holiday recreating the map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings. By coincidence, that is also 1m x 1.2m, and was drawn on a big piece of butcher’s paper! It hangs on the wall next to my map of Ely.

The Romans were the first to try to drain the Fens. How much evidence of their activities can still be seen in the landscape today?

Well, the Romans were first and foremost engineers, and they managed to tame many environments across Europe. But the might of Rome met her match with the fens! The landscape of the fens was too wild and impenetrable for the Romans to have any real success in their attempts to drain them.

However, the Romans did build several causeways to make travel easier, the most famous of which was the Fen Causeway, or Fen Road. This linked Denver, near Downham Market, to Peterborough, but it essentially was a road at the northern edge of the fens, which at that time would have been a coast road, as the modern coastline is many miles further north than it was in Roman times. Another causeway linked Cambridge with Ely, some of which is now part of the A10 trunk road and can be seen near Denny Abbey.

They also excavated the Cardyke (visible on my map). This canal system linked the Granta (now the Cam) to the West River and allowed movement of goods and people through the river system of the fens.

Since the marshes were drained in the seventeenth century it has obviously changed a great deal. How difficult was it to rediscover the medieval Fens?

It was harder than I expected. At first I simply tried searching online for a copy of how the fens would have looked, and that would have been sufficient for what I needed. But there were no definitive sources I could find. I also became aware that researchers had published material, but the information was not easily accessible.

What became apparent was that my task had two elements to it. The first was to try and understand how the land would have looked. This was relatively straightforward, as whilst the level of the water table has dropped since the fens were drained, the geology that created the “islands” has not changed at all (in other words, there has been no undue erosion of the landmass).

By far the most difficult part of the research was to try and understand how the waterways would have looked, and how they linked together. The river systems that people living in Ely today will recognise is very different to that of a thousand years ago. Today, the Ouse runs west to east and joins the Cam before heading North past Ely. The Cam (Granta) has not changed much since those times, but it came to light that the West River flowed east to west and joined the Great Ouse to head north to the left of Ely! This was a very different system to that seen today. The courses of the Ouse changed principally because of the two huge artificial drainage ditches that were constructed to the northwest of Ely (the Bedford Rivers), commissioned by the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1630 to help in the process of draining the fens.

By far the most difficult part of the research was to try and understand how the waterways would have looked, and how they linked together. The river systems that people living in Ely today will recognise is very different to that of a thousand years ago. Today, the Ouse runs west to east and joins the Cam before heading North past Ely. The Cam (Granta) has not changed much since those times, but it came to light that the West River flowed east to west and joined the Great Ouse to head north to the left of Ely! This was a very different system to that seen today. The courses of the Ouse changed principally because of the two huge artificial drainage ditches that were constructed to the northwest of Ely (the Bedford Rivers), commissioned by the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1630 to help in the process of draining the fens.

What sources did you use to delve into this lost landscape?

I used the resources of the British Library to look for the oldest maps of the area prior to the Dutch draining the fens in the 17th century. All maps of the area are thought to derive from a survey of the area carried out by William Hayward at the beginning of the 17th century. This map was destroyed in a fire, but it is believed that Sir Robert Cotton, a keen collector of fenland maps, had a copy made (The Cotton Map). It is an extraordinary document. Looking at the hand drawn map, you can see the lost Isle of Eels emerging from the fens, as if I was looking back in time.

I supplemented this information with a review of existing Ordnance Survey maps, using the 5-metre contour line to sketch out land that would have been above the ancient water table. In the British Library I came across a pivotal paper published by Major Gordon Fowler in 1934. This paper outlined the possible ancient watercourses of the area. Along with several other authors and notably the excellent Henry Darby, I pieced together how the rivers would have flowed around the island in Saxon times.

The final step was to add the main settlements that would have existed in 1071. For this I used a mixture of references from Domesday Book and the Liber Eliensis, the so-called Book of Ely, written in the 12th century by monks at Ely Abbey.

[NOTE: A full list of references can be found at the end of Rus’s article on the British Library’s blog.]

How much fieldwork did you have to do and what did that involve? How useful was it to be on the ground?

During the summer of 2013 I drove the back roads and lanes that criss-cross the island, making adjustments to my notes, extending the sweep of a hill, noting natural hollows in the ground, and removing the causeways and embankments that had been added much later. Without doubt, being on the ground helped add context to the map.

But for me, on a personal level, it was more than a matter of accuracy. Seeing the landscape allowed me to connect with the map, it helped guide my hand when I was back in my draughty cold loft, transcribing the information; it made the map live for me.

Were there any particularly unusual or surprising nuggets of information that you turned up in the course of your research?

Were there any particularly unusual or surprising nuggets of information that you turned up in the course of your research?

My discovery that the modern day Ouse had a completely different route and was not joined to the Cam surprised me. But to some extent, that was a matter of historical record, I simply needed the time to find the information.

However, some of the old books I read in the British Library gave vivid accounts of the fens in medieval times. The people were a breed apart; tough, independent, wary of outsiders. They wore eel skins to ward off illness and bad spirits. They would fight fiercely to defend their homes. The fens themselves were thriving with life, with bitterns, swans and eels. I read of Flag Iris, a beautiful carpet of flowers with a fragrant scent; but if a man stood on it, he would be sucked deep into the waters below. There was one account of a pod of whales that swam into the Granta from the sea. They became stuck in a small tributary and died. For many decades their skeletons were a reminder of the dangers of the fens.

So what did I do with all these nuggets? I am a writer, so I weaved them into my story, to bring it alive, to make it real.

How do you plan to use the map now that it’s finished?

Now that the map is complete (a copy of which I donated to the British Library), I can travel back in time to 1071 and see the Isle of Eels through the eyes of my characters. It has allowed me to be more credible when describing their adventures.

It is also my intention for the map to be part of the book, so that the readers can also see what Ely would have looked like in the eleventh century. Maybe one day, if my book is a success, the map will become as famous as the one of Middle Earth…

This week on the blog I’m pleased to be interviewing award-winning and bestselling historical novelist Elizabeth Chadwick, whose latest novel, The Winter Crown, the second volume in her Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, has just been published in the UK.

Eleanor (or Alienor as she was called by contemporaries, and as she is referred to in

This week on the blog I’m pleased to be interviewing award-winning and bestselling historical novelist Elizabeth Chadwick, whose latest novel, The Winter Crown, the second volume in her Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, has just been published in the UK.

The Winter Crown • Elizabeth Chadwick • Sphere • 496 pp. • £16.99

Eleanor (or Alienor as she was called by contemporaries, and as she is referred to in the novels) was one of the most influential and powerful women in twelfth-century Europe: a woman about whom much has been written over the centuries, and who has been variously portrayed on both stage and screen. Many assumptions have been made about her and yet relatively little is definitively known, as Elizabeth points out in the afterword to the first book in the trilogy, The Summer Queen.

Queen firstly to Louis VII of France and later to Henry II of England, Eleanor became the mother of no fewer than ten children, including King Richard I and King John. Elizabeth’s magnificent series explores the full sweep of her life, beginning with her first marriage at the age of just thirteen and her introduction to the cut and thrust of politics at the royal court. She delves into Eleanor’s character and brings to life a world that in many ways is thoroughly alien to our own, but that in others is so very familiar.

Earlier this year, Elizabeth hosted a Q&A with me on her website to coincide with the publication of The Splintered Kingdom in the United States. I’m delighted today to be able to return the favour, and to welcome her to the blog.

*

Firstly, what is it about the twelfth century that fascinates you?

It goes back to when I was a teenager. I had told myself stories from the moment I had vocabulary. I can remember making up tales around children’s picture books. An illustration would appeal to me and I’d make up a story about it, a bit like the Mary Poppins film where Mary and the children jump into the chalk pavement pictures. I’d make up new adventures inside my favourite illustrations. I did this throughout my childhood and into my teens. Sometimes I would take visuals and inspirations from TV programmes – a photograph of the Star Trek crew from the Radio Times, a still from the BBC production of Vanity Fair or The Last of the Mohicans.

As my teens advanced, the BBC put on a historical series titled the six wives of Henry VIII. I enjoyed this very much and began writing a Tudor story. However, that fell by the wayside after a few chapters. The following year the BBC screened a children’s programme titled Desert Crusader, dubbed from the French series Thibaud ou les Croisades. This was set in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and starred a knight of the mid-12th century, galloping round on his warhorse having exciting, sometimes romantic adventures. The hero to my fifteen year old self was truly gorgeous. I immediately began writing a novel with my protagonist loosely based on this character. Again rather like the chalk pictures, the story grew away from its origins and developed a complete life of its own. I didn’t know anything about the 12th century Holy Land so I had to head off to the library and begin researching. I wanted my story to feel as real as possible. Since my tale involved the hero returning to Europe, specifically to Angevin England, I had to research that aspect too, and that involved not only the political structure but all the detailed cultural background. I can remember being way too excited over finding a copy of Ewart Oakehott’s work on the archaeology of mediaeval weapons in the library and ignoring my A-level Tudor history homework to read up on 12th century swords!

As my teens advanced, the BBC put on a historical series titled the six wives of Henry VIII. I enjoyed this very much and began writing a Tudor story. However, that fell by the wayside after a few chapters. The following year the BBC screened a children’s programme titled Desert Crusader, dubbed from the French series Thibaud ou les Croisades. This was set in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and starred a knight of the mid-12th century, galloping round on his warhorse having exciting, sometimes romantic adventures. The hero to my fifteen year old self was truly gorgeous. I immediately began writing a novel with my protagonist loosely based on this character. Again rather like the chalk pictures, the story grew away from its origins and developed a complete life of its own. I didn’t know anything about the 12th century Holy Land so I had to head off to the library and begin researching. I wanted my story to feel as real as possible. Since my tale involved the hero returning to Europe, specifically to Angevin England, I had to research that aspect too, and that involved not only the political structure but all the detailed cultural background. I can remember being way too excited over finding a copy of Ewart Oakehott’s work on the archaeology of mediaeval weapons in the library and ignoring my A-level Tudor history homework to read up on 12th century swords!

Basically the more I read up on 12th century life and culture, the more I became interested in the period and the more I wanted to write stories set in that timeframe, so one fed off the other.

Do you think it’s an era that is sometimes overlooked?

I think it’s an era that is perhaps less mined than certain others, but it does have its share of novelists – my good friend Sharon Kay Penman for example. There are the Crowner John mysteries of Bernard Knight, or the novels of Ariana Franklin. And of course Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett. It also has its share of meaty historical incidents – the Anarchy period of the war between Stephen and Matilda, the reign of Henry II and the murder of Thomas Beckett, the Third Crusade. It has towering characters such as the great William Marshal, the loved and loathed Richard the Lionheart, and ditto his brother Prince and then King John. It was a tumultuous period of history, but it’s not quite Tudor territory in terms of saturation, and it does take a dedicated amount of researching. Sometimes people will say it takes less research but that’s not true. It probably takes more to actually understand the period and you have to dig a lot deeper to find what you’re looking for.

You paint a fascinating and complex portrait of your subject, Eleanor of Aquitaine. What attracted you to her and inspired you to choose her as the focus of your latest trilogy?

The Eleanor Vase, currently on display in the Louvre. It was given to Eleanor by her grandfather, William IX of Aquitaine, and she later gave it to her first husband, Louis VII of France as a marriage gift. (Photo credit: John Phillips.)

I was also interested in writing about Eleanor because scholarship is constantly turning up new information. For example, we now know she was more likely to have been 13 years old when she married, not 15 as has been earlier thought, and that puts a whole new slant on the way the character is portrayed. This is someone just out of childhood, a pawn in the power games of men, not a knowing, flirtatious older teenager as she has been so often portrayed. I felt there was a lot to be said that hasn’t been said before, and new, realistic ways of interpreting the material through the medium of fiction.

One of the things you do so well in the series is to bring to life the various conflicts, rivalries and alliances within the royal court. When dealing with so many characters, how do you keep track of all their relationships?

This is going to sound strange, I hope it doesn’t sound big headed – or perhaps I need a big head because the knowledge is all there in my mind! I sometimes have to pick up a reference book to check on a detail but on the whole it’s all there up top. I think it helps that I have been reading about and researching the period 1066-1220 since I was 15 and that’s a long time ago. It does mean that a lot of the history is already there and I can start researching from a strong, multi-layered bedrock. I do write a very detailed synopsis at the beginning of the novel and I can refer to this as a timeline so I guess that’s the skeleton part of the structure.

Mural depicting what is thought to be Henry II and his four sons in the chapel of St Radegonde at Chinon, Indre-et-Loire, France. (Photo credit: John Phillips.)

Some of the historical persons featured in your latest series may be familiar to readers of your earlier novels. Do you ever revise your opinion of particular characters, and does that affect how you portray them in your writing?

Yes. I think we are always learning. Personally, what might have been true of my knowledge 10 years ago may now have changed down to new historical discoveries or increased study and awareness on my part. I wrote a novel called The Champion which is one of my earlier slightly more romantic works where I cut Prince John a little more slack than I would now. But at the same time I probably understand more about John and his personality now and can bring that to bear when writing his character today, so he’d be more nuanced. Sometimes there’s a conundrum when a character has to change hair or eye colour because of new research but if that happens there’s always the author’s note to explain it. I wrote a couple of novels about the Bigod family – The Time of Singing and To Defy A King, where one of my characters, Roger Bigod goes through changes as he ages and life takes its toll on him. I’ve had readers say why is he so different from one novel to the next, but I don’t think he is. It’s just that we grow and change and perhaps become less flexible as we get older. So with a character, if one is being realistic, one has to take into account the changes wrought by time and experience. I go with the truest version I know at the point of writing and make up for discrepancies in the afterword should I need to.

Henry II and Eleanor ruled over a territory that famously stretched from the Scottish Borders to the Pyrenees. How did they maintain their authority over such far-flung lands?

The Summer Queen, the first book in Elizabeth’s Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, is available now in paperback, published by Sphere.

Are there any reference books you can recommend for readers interested in finding out more about Eleanor and her world?

England under the Norman and Angevin Kings • Robert Bartlett

I understand that you are currently writing the final book in the trilogy, The Autumn Throne. What’s next for you?

I’ve discussed the next novels with my publisher, and I can say for definite that William Marshal and his family are once more on the cards. There are gaps in his life that need filling in and I’ve already started research into the background!

*

Many thanks, Elizabeth, for taking the time to talk about your work! The Winter Crown is available now in hardback and as an ebook, published by Sphere. The first book in the trilogy, The Summer Queen, is also available in paperback.