It’s that time of year again! Following on from 2011’s top historical reads, I’ve selected a few of the books that I’ve most enjoyed in 2012: new releases as well as old favourites, some of them historical and some of them not. Here are a couple to get you started. I’ll be posting some more of my recommendations before the end of the year, so watch this space for Part Two coming soon!

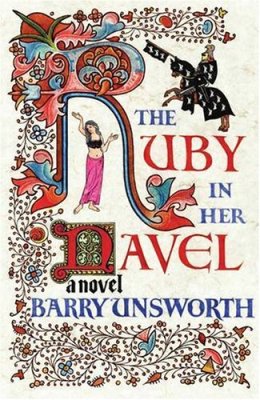

The Ruby in Her Navel

The Ruby in Her Navel

Barry Unsworth

Penguin, 336 pp., £7.99

Paperback

Set in the twelfth-century in the young Kingdom of Sicily, this novel by the late Barry Unsworth, who died earlier this year, is the tale of a Norman would-be knight named Thurstan Beauchamp. A purveyor of entertainments, envoy and occasional spy attached to the palace administration of King Roger II, he is ambitious but naive, and it is because of those very qualities that he soon finds himself caught up in a web of deceit, treachery and conspiracy.

Brilliantly evocative and skilfully written, The Ruby in Her Navel captures a sense of the religious, political and cultural tensions undermining the nascent kingdom. Unsworth’s facility with description is second to none, and the sights and sounds and smells of Thurstan’s world are brought to life in vivid fashion. For those with an interest in medieval fiction, there are few novels I can recommend more highly.

I first read this book in 2007, as I was just embarking on the novel that would later become Sworn Sword. It was a real inspiration for me at the time, and, even when I came to read it for a second time earlier this year, it didn’t disappoint. For a fuller review, click here.

Collapse

Collapse

Jared Diamond

Penguin, 590pp., £9.99

Paperback

My top non-fiction read of the year, Collapse seeks to explain how and why mighty civilisations have fallen in the past, and what lessons we might learn from their failures.

Drawing on examples from both recent and ancient history, Diamond, who is Professor of Geography at UCLA, explores the various forces – cultural, political and environmental – that led to the demise of societies in the past. His researches take him all across the globe, from the lost civilisations of Easter Island and Norse Greenland to modern China, Australia and Haiti, all of which are facing many of the same struggles.

It’s a fascinating and in-depth study which offers plenty of food for thought about our modern lifestyles, and how Western civilisation needs to adapt if it is to survive the pressures of resource depletion, pollution and climate change. A must-read.

A piece by Colin Burrow in the latest edition of the London Review of Books (22 November 2012) asks, “Why does a name sound right? … Are there rules about how names are given to characters?”

I’m often asked at talks and readings how I go about choosing the names for my characters. This can be a bit trickier for historical novels than for modern fiction, and inevitably involves a fair amount of research. Whilst a lot of medieval names are still in use today in some form – especially French names imported by the Normans, like William, Stephen and Hugh – others, particularly Anglo-Saxon names like Ælfwold or Byrhtwald, are no longer in use. So to uncover interesting examples that I can use in my novels, I go back to the primary sources and gradually build up a database of Anglo-Saxon, Norman, Breton and Welsh names. Domesday Book, which was compiled in 1086, is an ideal resource for the Norman Conquest, as are the various contemporary chronicles.

But that’s only part of the story. It’s important for me to choose a name that fits the personality of the character I have in mind. I knew that for Tancred’s trusted brother-in-arms Wace, for example, I wanted a single-syllable name to reflect his blunt manner, and there were surprisingly few to choose from in my database. “Wace” had the advantage that it rhymed with “mace”: a bludgeoning weapon and a relatively unsubtle one at that, making use of brute strength to batter one’s opponent. All of those connotations fitted well with my idea of what I wanted the character to be like.

Obviously it’s not an exact science – there are of course many more words that rhyme with Wace, all of which might have suggested different aspects to his character, but that was the one that first sprang to mind, and so that association stuck with me. For very similar reasons I chose to call one of Tancred’s knights in The Splintered Kingdom Serlo largely because of its similarity to “surly”, which was how I originally imagined him, although that impression changed in the course of writing the rest of the novel.

Other names evolve over time. My narrator and hero was originally (in the very earliest drafts of the first chapter of the novel that eventually, several years later, became Sworn Sword) named Thurstan, partly in homage to the Norman protagonist of Barry Unsworth’s 2006 novel The Ruby in Her Navel, set in twelfth-century Sicily, which was one of the books that inspired me to start writing my own historical fiction. But very quickly I realised that Thurstan didn’t feel quite right. I wanted to define my narrator as distinct from Unsworth’s, and give him an independent identity, which meant I had to give him a new name.

So I went back to my list of French names, and came up with Tancred. Somehow, it sounded stronger, bolder and grittier, and just, well, … right. And although it’s fairly obscure now, it was a noble name at the time, being also the name of one of the leaders of the First Crusade, Tancred, Prince of Galilee, and of a King of Sicily in the following century. And so I began to build a picture of my Tancred as someone with ambition and aspiration to great things.

There were problems with that choice later on, especially when I decided he was to be of Breton extraction rather than a Norman, which meant that I had to explain why he had a French and not a Breton name. But the explanation that I came up with in turn helped to shape his character and his background, and add new dimensions to him that I hadn’t considered before. Usually, as in the case of Wace, it’s the other way around, but occasionally the choice of name itself will give me inspiration as to the personality of a character and the direction in which his story might unfold.

I should note that I generally prefer to use the contemporary eleventh-century rather than modern forms of personal names, so as to make them seem less familiar and also, in the case of the Norman characters, more foreign and less English. So William becomes Guillaume, Hugh becomes Hugues, Edgar becomes Eadgar, Edith becomes Eadgyth and so on. In a similar way, as far as possible I use the Old English versions of place-names, to add distance and remind readers that the England of c.1066 was a very different country to the England of today.

One last point: once a character’s name is established, I find it very difficult to change it unless there’s very good reason to do so. Why this is, I’m not really sure, although probably it’s precisely because the name is usually so intrinsically tied up with his or her personality that to alter it would simply feel wrong, in some way like a betrayal of that character. I just can’t bring myself to do it.

During the course of 2006-7, when I was first laying pen to paper on the early drafts of the manuscript that would become Sworn Sword, I was fortunate enough to read a number of historical novels that really inspired me. In recent weeks I’ve been revisiting a few of those novels, to see if they still hold the same fascination for me five or so years on, and whether with the benefit of more writerly experience I view them any differently now.

Among those books were titles by Bernard Cornwell, C. J. Sansom, and Robert Harris, set in periods ranging from Rome in the late Republic to Tudor England. Particular inspiration, however, came from The Ruby in Her Navel by celebrated British author Barry Unsworth.

Among those books were titles by Bernard Cornwell, C. J. Sansom, and Robert Harris, set in periods ranging from Rome in the late Republic to Tudor England. Particular inspiration, however, came from The Ruby in Her Navel by celebrated British author Barry Unsworth.

Longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2006, it’s set in mid-12th century Sicily in the reign of King Roger II, more than seventy years after the Norman conquest of the island, in a brief and peculiar (for the Middle Ages) period of toleration that saw various ethnic and religious groups – Normans, Italians, Saracens and Byzantine Greeks; Muslims, Jews and both Western (Latin) and Orthodox Christians – co-existing in apparent harmony despite the political fallout from the recent failure of the Second Crusade. More specifically, it’s the story, told in the first person, of a young would-be knight named Thurstan Beauchamp, who works as a purveyor of entertainments and occasional envoy and spy – for want of better terms – attached to the Diwan (Office) of Control in the palace administration.

What unfolds is a tapestry of competing nobles, royal officials, churchmen, all with their own ambitions and plans for advancement: a shadowy assortment of real and imagined foes with the means to destabilise King Roger’s realm from within and without. Through those tangled webs the trusty, proud and not a little naive Thurstan makes his way, but soon he finds himself embroiled in a plot that threatens to destroy all he holds dear. There are the added complications, too, of the two women in his life: Thurstan’s childhood sweetheart Lady Alicia, recently widowed and returned from Outremer; and the exotic and enchanting Anatolian belly-dancer Nesrin, whose troupe he employs to entertain at the king’s court.

This a carefully crafted portrait of an unusual place and time in history. Unsworth’s descriptive powers and his ability to evoke all the senses are second to none. His wide-ranging settings – from the richness of the palace at Palermo or the elaborate gardens at Favara to the dusty streets of the port of Bari in Apulia – are desribed in vivid detail. The Ruby in Her Navel showed me the power of historical fiction to evoke the spirit of a distant age and to bring the past to life, and even on a second reading it did not disappoint.

Thurstan’s world is a complex and uncertain one in all sorts of ways: politically, religiously and morally. By choosing to tell the story in the first person from his perspective, Unsworth allows us to glimpse something of the various dark forces that are at work without ever fully comprehending them, as well as to engage on an intimate level with the realities of life in that age and the burning issues of the day. It’s skilfully done, and while Thurstan is undoubtedly a flawed hero – vain, overly confident in his own abilities, and too trusting by half – he nevertheless manages to be a character with whom it is possible to sympathise.

For those with an interest in medieval fiction, there are few novels I can recommend more highly. The Ruby in Her Navel remains one of my all-time favourites.

NOTE: In an unexpected and very sad turn of events, the day after I posted this review (8 June) the news broke that Barry Unsworth had died at the age of 81 in Perugia, Italy. Even though it wasn’t my intention, I hope that my above words will stand as a tribute, however small, to his life and to his qualities and skill as a writer. He will be sorely missed by his many fans.