On Saturday 23 April, Viking scholars and other interested parties (myself among them!) will be gathering at the University of Nottingham for the twelfth annual Midlands Viking Symposium: a day of talks on all aspects of the Viking Age, given by experts in their field.

Booklets from the Languages, Myths and Finds conference – another Viking-themed University of Nottingham event – which took place in 2014.

Like the London Anglo-Saxon Symposium, which I blogged about earlier this year, MVS is all about bringing some of the latest historical research to a wider audience.

This year’s theme is Interpreting the Viking Age, and there are set to be talks on subjects including: the famous Oseberg ship; Norse place-names in Britain and abroad; and how British history from the Viking Age was recorded and remembered in the Icelandic sagas. There will also be a resident craftsman, Adam Parsons – archaeologist and living history enthusiast – talking about replica Viking artefacts, and how the originals would have been used.

The programme runs from 10am to 5pm and includes lunch and refreshments, and at only £30 is terrific value. This year will be the third year I’ve attended MVS – having previously been to the 2013 and 2014 events. Each time I’ve come away armed with new knowledge and new ways of thinking about the period (not to mention reams of notes, too!), much of which has found its way in one form or another into my new novel.

For more information about MVS 2016, including the provisional programme, or to register for the Symposium, visit the event page on the University of Nottingham website.

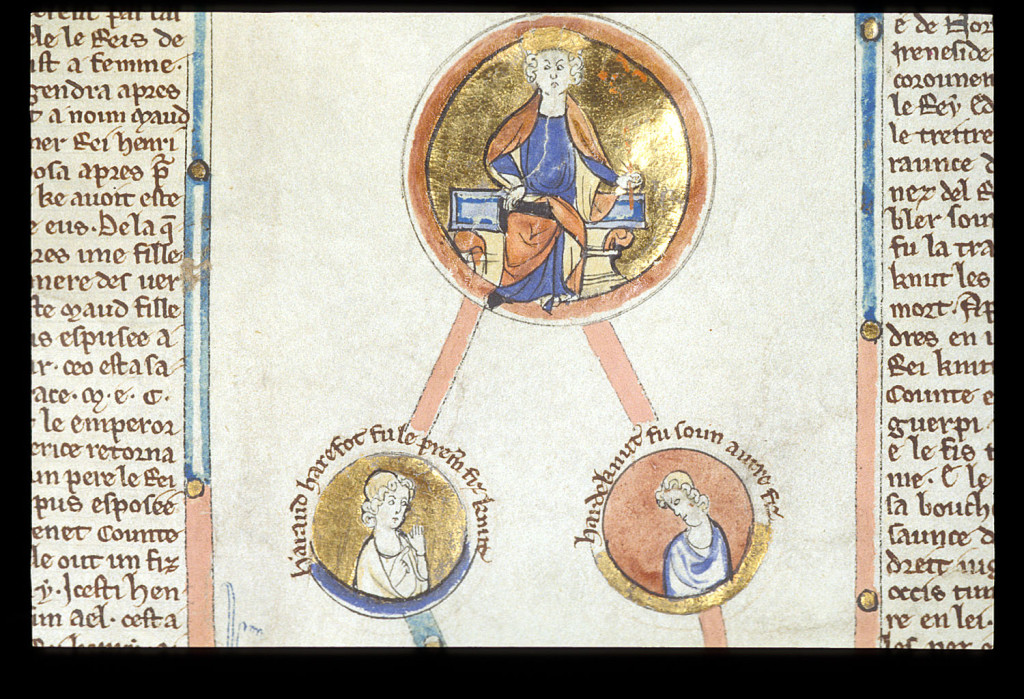

Cnut (1016-35) and his sons Harold Harefoot (1035-40) and Harthancut (1040-2), depicted in a genealogical roll from the late 13th century (Royal 14 B V Membrane 4).

MVS won’t be my only trip to Nottingham this year, either. I’m pleased to say that I’ve been invited by Dr Christina Lee (@NorseLass) to speak at a conference in late June and early July on The Viking World: Diversity and Change, as part of a round table discussion on academic research and historical fiction, which I’m looking forward to enormously. More news on that soon!

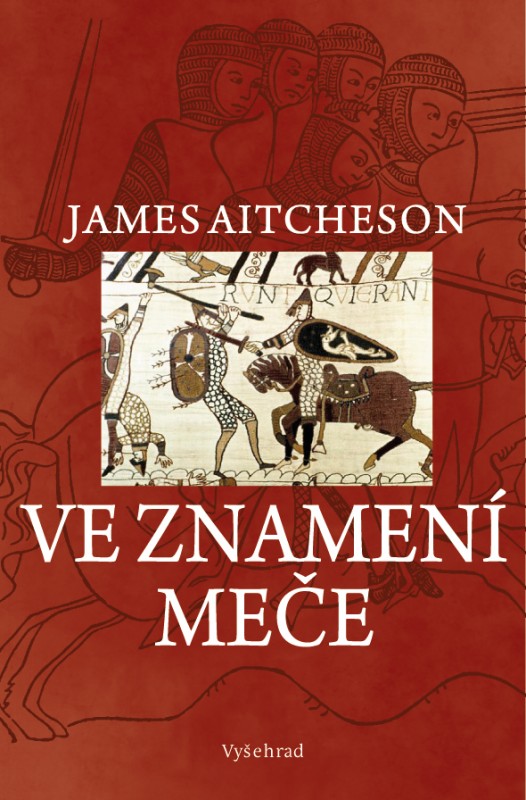

My first new book of 2016 is almost here! I’m pleased to announce that Ve znamení meče, the Czech edition of Sworn Sword, will be published next month, and that this will be the cover:

Ve znamení meče • James Aitcheson • Vyšehrad • 432 pp. • Hardcover • 368 Kč

As you can see, it’s very different to the cover of both UK and US editions, and to that of the German edition as well, but I think you’ll agree it’s striking in its own way. It’s difficult to go wrong with such a widely known image as the Bayeux Tapestry!

Translated by Petra Pachlová, Ve znamení meče will be published by Vyšehrad in hardcover on 15 February 2016 and can be yours for a mere 368 Kč (around £10). Spread the word among your Czech-speaking friends!

For a fuller synopsis and further details, and to buy online, visit the Vyšehrad website.

As I write this, I’ve just booked my place on the fifth annual London Anglo-Saxon Symposium, which will be taking place on Saturday 12 March, hosted by the Institute of English Studies at the University of London.

King Cnut (r. 1016-35), depicted with his wife, Queen Emma, in the New Minster Liber Vitae.

An afternoon of lectures representing some of the latest research into aspects of early medieval England, the Symposium is always a fun and informative event. I’ve been to it each of the last three years, and every time it’s opened my eyes to new ways of thinking and avenues of study that I hadn’t thought about before. The best part is that it’s only £12 to attend!

If Vikings are your thing, you’ll be pleased to hear that this year’s theme is Anglo-Scandinavian England. Among the topics under discussion will be: Viking ships; identities in Anglo-Scandinavian England; and the impact and influence of Old Norse upon the English language.

To see the full programme for this year’s Symposium – including abstracts for each of the papers – and to register, visit the LASS page at the Institute of English Studies.

Also, you might like to see my introduction to London c.1066, which was partly inspired by Dr Michael Bintley’s walking tour of the capital that formed part of the 2014 Symposium.

With 2015 behind us, it’s that time of year when I reveal what I’ve been reading in the last twelve months. As usual with these lists, my picks weren’t necessarily all published during the past year, but represent a mix of older titles as well as some new releases.

Unusually there’s only one historical novel among my fiction picks, which simply reflects my choice of reading material over the year, although my non-fiction selections cover the Neolithic, medieval and modern periods.

If you’ve enjoyed any of the titles below or would like to share your own favourite books of 2015, feel free to join in the discussion on Twitter (@JamesAitcheson) or on Facebook. You can also take a look back at my fiction and non-fiction picks of 2014.

Fiction

Never Let Me Go

Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro

Faber & Faber, 304 pp., £8.99

Paperback

The best fiction grabs you from the opening page, sometimes through a narrative hook, although much more often it’s the voice established by the author that compels me to read on. That was the case with Never Let Me Go, which from the very first paragraph never let me go.

In many ways reminiscent of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, which I greatly admire, Ishiguro’s haunting novel is the story of Kathy H, 31, a ‘carer’ reflecting on her time growing up as a student at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school in rural England that is not all that at first it seems. There are no holidays; no parents ever visit; the teachers are always referred to as ‘guardians’; the curriculum followed is far from standard; and children and adults alike are only ever referred to by their first names.

This is a difficult book to review without spoilers. Suffice it to say, though, that these idyllic surroundings mask a dark secret regarding the destiny of the children. Through the lens of Hailsham, Ishiguro is posing his version of the eternal question: what is the meaning of our existence? Kathy, by her own admission, has led a healthy, fulfilling and purposeful life. She’s pleased to have been given the chance to help others, to have enjoyed close friendships, and to know – as the guardians at Hailsham tell all the students – that she is special.

And yet a dark cloud hangs over the novel: a sense of betrayal and resentment, never explicitly stated or acknowledged but present just below the surface. Ishiguro’s greatest success in Never Let Me Go lies in conveying, in conversational, unhurried and considered prose, exactly that complex and never-fully-resolved web of sentiment.

Ultimately, I feel – and here others may well disagree – that Never Let Me Go doesn’t completely deliver on its early promise. In the final act, as revelations are made, it becomes harder and harder to avoid questioning aspects of the underlying premise. Nevertheless, this is a tender, thought-provoking novel, and one of my favourite books of 2015.

The Road

The Road

Cormac McCarthy

Picador, 320 pp., £8.99

Paperback

With so many books out there and so little spare time in which to enjoy them all, it’s not often that I choose to re-read even a favourite one. The Road – one of the key inspirations behind my own forthcoming fourth novel – is an exception to that rule, and in fact is one of the few books that I have actually enjoyed more on a second reading.

Set in a future America after an unknown cataclysm, an unnamed man and his son journey towards the coast through a burnt landscape, devoid of life save for the cannibals and slavers prowling the roads. Starving, weak and cold, their only hope of survival in this hostile environment is if they stay together.

Related in minimalist prose, their story is all the more powerful for what goes unsaid. The nature of the apocalypse that brought about such devastation is only hinted at obliquely, but in a sense it is unimportant: the past is irrelevant; only the present matters.

While the subject matter may be bleak, however, hope is never lost completely. Yes, there is much greed, cruelty and selfishness in the world envisioned by McCarthy, but in spite of that there is still goodness, love, belief and self-sacrifice. Even in the very worst of times, he argues, the human spirit can never be conquered.

Also recommended:

- Marina Lewycka’s first novel, A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian, which was shortlisted for the 2005 Orange Prize;

- Moral Disorder, a brilliant and sensitive collection of linked short stories, set over a span of six decades, by Margaret Atwood;

- Claire Lowdon’s critically acclaimed debut novel, Left of the Bang, about the angst, misunderstandings and infidelities of a group of young London-dwellers;

- The Orenda, Joseph Boyden’s novel set in 17th-century Canada, which tells of the arrival of French missionaries and colonists, and their impact upon the native peoples.

Non-fiction

On Silbury Hill

On Silbury Hill

Adam Thorpe

Little Toller, 232 pp., £15.00

Hardcover

Part memoir, part history, part travelogue: Adam Thorpe’s On Silbury Hill defies categorisation. A unique book in so many ways, it charts the many ways in which the eponymous Wiltshire monument – the largest man-made mound in Europe – has been viewed through the centuries.

Taking as a starting-point his first encounters with the Hill while a boarder at the nearby Marlborough College, Thorpe offers a lyrical, highly personal response to the Neolithic landscape in which it is set. As well as reflecting upon what archaeology has had to say about the site, he also delves into rituals and superstitions both ancient and modern in an attempt to unravel something of its meaning and purpose.

As someone who grew up in the vicinity of Silbury and is familiar with the various places described, this book had particular resonance for me. Whether it would have the same appeal to a non-local is hard to say, but it is hard not to be ensnared by Thorpe’s prose, which communicates so effectively his wonder and reverence for this most ancient of British monuments.

It’s worth noting, too, that the book itself is a beautiful object: a diminutive hardcover enriched throughout with photographs and artists’ impressions of the monument and the surrounding landscape. A real gem.

The Inheritance of Rome

The Inheritance of Rome

Chris Wickham

Penguin, 688 pp., £14.99

Paperback

In this sweeping, magisterial history covering six centuries from AD 400 to the end of the first millenium, Chris Wickham sets out to demonstrate why the so-called Dark Ages were anything but. While this period is traditionally characterised as being one of disorder and invasion, it also witnessed – as all early medieval scholars know well – a wide variety of new expressions of creativity and culture.

With its main text running to 560 pages, this is perhaps as concise as it is possible to make a history of Europe that spans such a broad period. As one might expect, it’s dense, but given its geographical and chronological scope – from the fragmentation of the western Roman empire, via the rise of successor kingdoms and the emergence of Islam, to the ‘feudal’ world – this is a book that arguably should be dipped into, chapter by chapter, rather than read continuously.

Some readers may be disappointed by the lack of an overarching narrative to help bind such a wealth of material together, but this runs counter to Wickham’s philosophy, which is to steer clear of imposing such traditional frameworks on this period. Instead, he favours a bottom-up approach: one that assesses the peoples, kingdoms and cultures of the period on their own terms, rather than with reference to what preceded and succeeded them.

Detailed maps and colour plates help provide context to the information presented, while the endnotes and bibliography, which stretch to nearly 60 pages, make this an excellent springboard for those wishing to delve further into the early Middle Ages.

Also recommended:

- The Early Middle Ages, edited by Rosamund McKitterick, which provides a useful counterpoint to Wickham, tackling the same period through themes (politics, economy, religion etc.) rather than dividing it up according to geography;

- The Cambridge Introduction to Anglo-Saxon Literature, Hugh Magennis’s excellent guide to the literary world of Bede, Beowulf and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

- Stephen Aron’s The American West: a Very Short Introduction, exploring the complex history of the region from the precolonial era to the twentieth century;

The US paperback edition of The Splintered Kingdom hits bookstores today! Published by the wonderful team at Sourcebooks Landmarks, it can be yours for the meagre sum of $15.99, available from all good bricks-and-mortar and online retailers. (Ebook editions are also available for all platforms.)

The Splintered Kingdom is the second book in the Conquest Series, featuring the knight Tancred and his quest for vengeance after his lord is murdered by English rebels. One year on from the end of Sworn Sword, Tancred has been rewarded for his exploits with a manor in the turbulent Welsh borderlands.

The Splintered Kingdom is the second book in the Conquest Series, featuring the knight Tancred and his quest for vengeance after his lord is murdered by English rebels. One year on from the end of Sworn Sword, Tancred has been rewarded for his exploits with a manor in the turbulent Welsh borderlands.

But Tancred’s hard-fought gains are soon placed in peril as a coalition of enemies both old and new prepares to march against King William. With English, Welsh and Viking forces gathering and war looming, Tancred is chosen to spearhead a perilous expedition. Success will bring him glory beyond his dreams; failure will mean the ruin of the reputation he has worked so hard to forge.

As shield walls clash and the kingdom burns, not only is Tancred’s destiny at stake, but also that of England itself.

Norman knights, Duke William among them, get ready for action at the 2015 Battle of Hastings re-enactment.

Recently I was invited by Dr Charles West (@Pseudo_Isidore) of the University of Sheffield to write a guest post for the Department of History’s blog, History Matters.

Inspired by my annual visit to English Heritage’s Battle of Hastings re-enactment in Sussex (pictured above), and by a heated discussion on last week’s Start the Week on BBC Radio 4 about the value of historical fiction, I penned a piece on the subject of ‘truth’ in history and fiction, and why the two disciplines should be able to coexist:

Historical fiction and alternative truths

James Aitcheson

If you have any thoughts on the subject, please do join in the discussion by leaving a comment. You can also follow Sheffield’s Department of History on Twitter (@unishefhistory).