Earlier this month I was thrilled to be invited back to Huddersfield New College in West Yorkshire for a second year in a row to give an event as part of their celebrations for World Book Day, which fell this year on Thursday 3 March.

As last year, I not only gave a talk

Earlier this month I was thrilled to be invited back to Huddersfield New College in West Yorkshire for a second year in a row to give an event as part of their celebrations for World Book Day, which fell this year on Thursday 3 March.

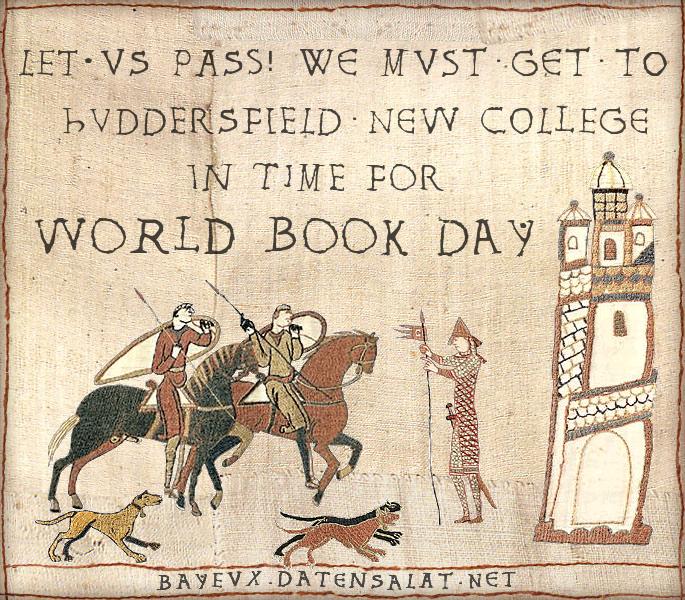

A previously undiscovered section of the Bayeux Tapestry.

As last year, I not only gave a talk to Year 12 and 13 History students about Anglo-Saxon England, but also ran a creative writing workshop for aspiring poets and prose writers, focussing on overcoming the fear of the blank page and on letting the imagination run wild.

The workshop involved a series of short exercises including a 3-minute free writing sprint, and various word- and picture-based challenges, after each of which we shared what we’d written with the rest of the group. It was a huge amount of fun not just for the students but also for me. As always in these sessions, I was massively impressed by the richness and diversity of the writing that emerged, and I hope that the students went away as energised and full of ideas as I did.

The writing workshop was a huge success, and tremendous fun too. Photo credit: Rebecca Wilson.

I was also given the honour of presenting the certificates at a lunchtime prizegiving ceremony to the winners – as chosen by staff – of the College’s annual short story competition. Needless to say it was a hectic day but also hugely enjoyable, and I’d like to thank the College librarian, Rebecca Wilson, for organising the event, as well as Mark Sheridan, Jean Westacott and the Principal, Angela Williams, for making me feel so welcome.

Presentation of the certificates for the winning entries in the student short story competition. Photo credit: Rebecca Wilson.

Recently I was invited by Dr Charles West (@Pseudo_Isidore) of the University of Sheffield to write a guest post for the Department of History’s blog, History Matters.

Inspired by my annual visit to English Heritage’s Battle of Hastings re-enactment in Sussex (pictured above), and by a heated discussion on last week’s

Norman knights, Duke William among them, get ready for action at the 2015 Battle of Hastings re-enactment.

Recently I was invited by Dr Charles West (@Pseudo_Isidore) of the University of Sheffield to write a guest post for the Department of History’s blog, History Matters.

Inspired by my annual visit to English Heritage’s Battle of Hastings re-enactment in Sussex (pictured above), and by a heated discussion on last week’s Start the Week on BBC Radio 4 about the value of historical fiction, I penned a piece on the subject of ‘truth’ in history and fiction, and why the two disciplines should be able to coexist:

Historical fiction and alternative truths

James Aitcheson

If you have any thoughts on the subject, please do join in the discussion by leaving a comment. You can also follow Sheffield’s Department of History on Twitter (@unishefhistory).

What makes a great first sentence? What do people look for in the opening of a novel? How do authors grab readers’ attentions and entice them to read on?

These were some of the questions I posed last week when I visited Marlborough College to lead a two-day creative writing workshop for a group of

What makes a great first sentence? What do people look for in the opening of a novel? How do authors grab readers’ attentions and entice them to read on?

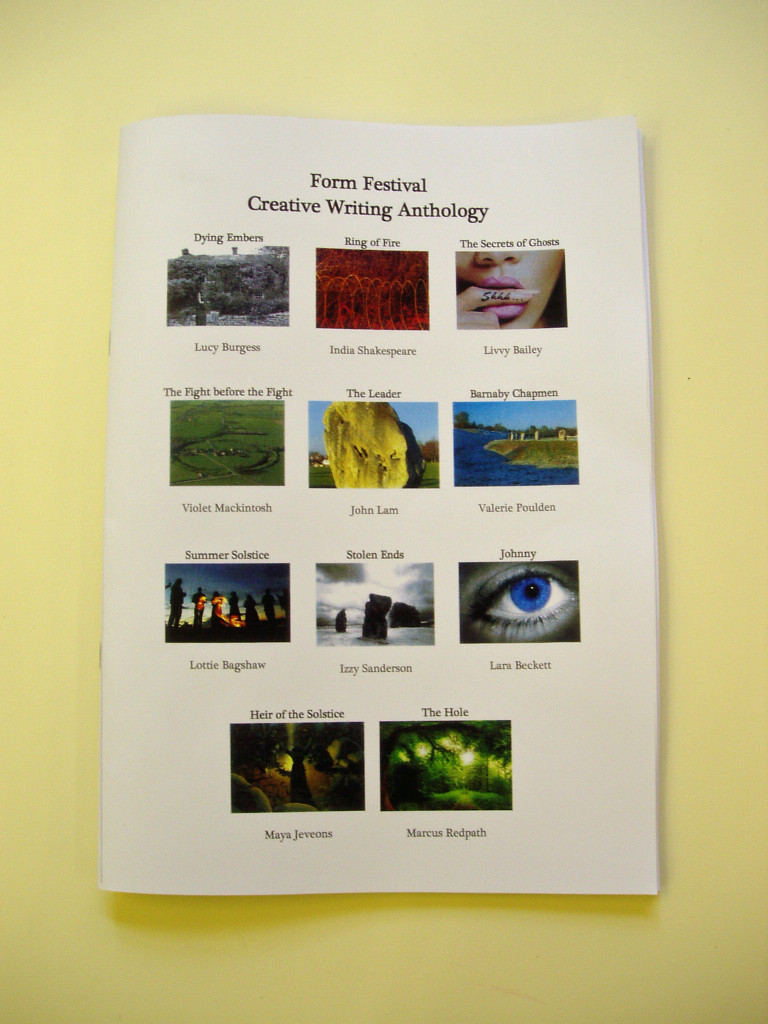

These were some of the questions I posed last week when I visited Marlborough College to lead a two-day creative writing workshop for a group of Year 9s as part of their summer term’s Form Festival. The ancient monuments at nearby Avebury provided the inspiration, the students provided the creativity, and the end result was the very smart-looking anthology pictured here!

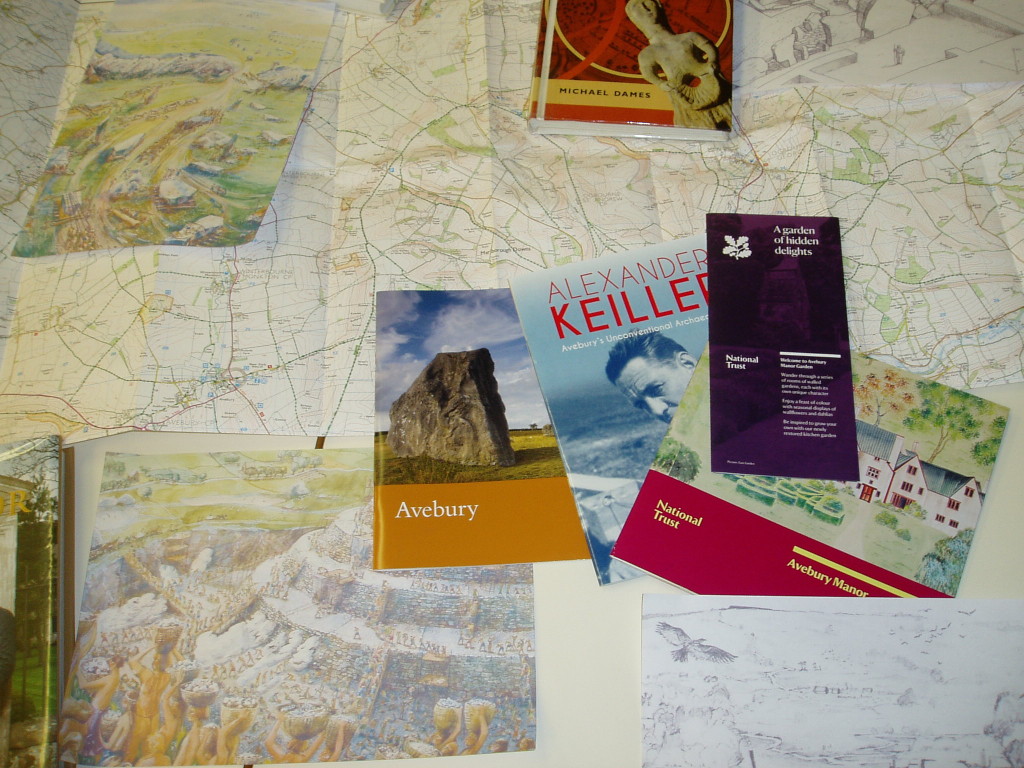

After spending a few hours exploring the ancient stones and the museums at Avebury, and trying to imagine the kinds of people who might have lived there through the ages, we returned to the College in the afternoon armed with character concepts and the seeds for possible plots.

With guidance, suggestions and feedback from me, the students then started to use the ideas they’d come up with to write a short story or the first chapter of a novel. At the end of the second day, all the pieces, complete with blurbs and front covers, were collected into the volume shown above, which was printed for the rest of the school to read and enjoy.

One of the two Portal Stones at Avebury, Wiltshire.

Although the main focus of the workshop was historical fiction, the students were encouraged to let their imaginations run wild and to write in whatever genre they liked, so long as their stories were connected in some way to Avebury.

What emerged from the workshop was an amazing outpouring of creativity. The tales produced took place in all periods of history, from the Neolithic to the Viking Age to the modern day; they featured supernatural forces, ancient rituals, long-forgotten battles, mysterious ruins, and a diverse range of characters including druids, archaeologists and a prehistoric proto-suffragette rebelling against the traditions of her tribe.

Some of the research materials used to generate ideas, including maps, artists’ renderings and (of course) books!

Thanks to everyone at Marlborough College for making me feel so welcome over the two days I was there. It was a pleasure to work with such an enthusiastic group of writers, and I wish them the best of luck for the future.

*

Earlier this year, I was invited to give a talk about the Norman Conquest and also to run a creative writing workshop at Huddersfield New College to celebrate this year’s World Book Day.

The creative writing session was based around a series of short, fun challenges designed to help free up the imagination, spark ideas and (above all) overcome the fear of the blank page – an affliction that strikes all authors from time to time.

Here I am with the creative writing group at Huddersfield New College

on World Book Day 2015. Photo credit: Huddersfield New College.

I was blown away with the range and quality of writing produced in response to the various challenges I set. The workshop was enormous fun for me as well as for the students, as I think you can tell from our grins in the photo above, taken at the end of the workshop.

As at Marlborough, the welcome I received from both staff and students in Huddersfield was absolutely terrific. With any luck my being there will have inspired a few to go on to study History or to develop their writing further! I certainly felt very privileged to be in the presence of so many talented young authors, and I hope to be able to return in the not too distant future.

*

If you’d like to get in touch about organising a creative writing workshop at your school, college, library or festival, you can do so via the Contact page.

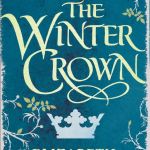

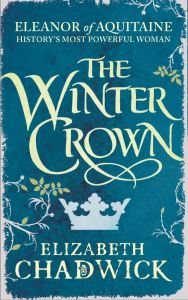

This week on the blog I’m pleased to be interviewing award-winning and bestselling historical novelist Elizabeth Chadwick, whose latest novel, The Winter Crown, the second volume in her Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, has just been published in the UK.

Eleanor (or Alienor as she was called by contemporaries, and as she is referred to in

This week on the blog I’m pleased to be interviewing award-winning and bestselling historical novelist Elizabeth Chadwick, whose latest novel, The Winter Crown, the second volume in her Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, has just been published in the UK.

The Winter Crown • Elizabeth Chadwick • Sphere • 496 pp. • £16.99

Eleanor (or Alienor as she was called by contemporaries, and as she is referred to in the novels) was one of the most influential and powerful women in twelfth-century Europe: a woman about whom much has been written over the centuries, and who has been variously portrayed on both stage and screen. Many assumptions have been made about her and yet relatively little is definitively known, as Elizabeth points out in the afterword to the first book in the trilogy, The Summer Queen.

Queen firstly to Louis VII of France and later to Henry II of England, Eleanor became the mother of no fewer than ten children, including King Richard I and King John. Elizabeth’s magnificent series explores the full sweep of her life, beginning with her first marriage at the age of just thirteen and her introduction to the cut and thrust of politics at the royal court. She delves into Eleanor’s character and brings to life a world that in many ways is thoroughly alien to our own, but that in others is so very familiar.

Earlier this year, Elizabeth hosted a Q&A with me on her website to coincide with the publication of The Splintered Kingdom in the United States. I’m delighted today to be able to return the favour, and to welcome her to the blog.

*

Firstly, what is it about the twelfth century that fascinates you?

It goes back to when I was a teenager. I had told myself stories from the moment I had vocabulary. I can remember making up tales around children’s picture books. An illustration would appeal to me and I’d make up a story about it, a bit like the Mary Poppins film where Mary and the children jump into the chalk pavement pictures. I’d make up new adventures inside my favourite illustrations. I did this throughout my childhood and into my teens. Sometimes I would take visuals and inspirations from TV programmes – a photograph of the Star Trek crew from the Radio Times, a still from the BBC production of Vanity Fair or The Last of the Mohicans.

As my teens advanced, the BBC put on a historical series titled the six wives of Henry VIII. I enjoyed this very much and began writing a Tudor story. However, that fell by the wayside after a few chapters. The following year the BBC screened a children’s programme titled Desert Crusader, dubbed from the French series Thibaud ou les Croisades. This was set in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and starred a knight of the mid-12th century, galloping round on his warhorse having exciting, sometimes romantic adventures. The hero to my fifteen year old self was truly gorgeous. I immediately began writing a novel with my protagonist loosely based on this character. Again rather like the chalk pictures, the story grew away from its origins and developed a complete life of its own. I didn’t know anything about the 12th century Holy Land so I had to head off to the library and begin researching. I wanted my story to feel as real as possible. Since my tale involved the hero returning to Europe, specifically to Angevin England, I had to research that aspect too, and that involved not only the political structure but all the detailed cultural background. I can remember being way too excited over finding a copy of Ewart Oakehott’s work on the archaeology of mediaeval weapons in the library and ignoring my A-level Tudor history homework to read up on 12th century swords!

As my teens advanced, the BBC put on a historical series titled the six wives of Henry VIII. I enjoyed this very much and began writing a Tudor story. However, that fell by the wayside after a few chapters. The following year the BBC screened a children’s programme titled Desert Crusader, dubbed from the French series Thibaud ou les Croisades. This was set in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and starred a knight of the mid-12th century, galloping round on his warhorse having exciting, sometimes romantic adventures. The hero to my fifteen year old self was truly gorgeous. I immediately began writing a novel with my protagonist loosely based on this character. Again rather like the chalk pictures, the story grew away from its origins and developed a complete life of its own. I didn’t know anything about the 12th century Holy Land so I had to head off to the library and begin researching. I wanted my story to feel as real as possible. Since my tale involved the hero returning to Europe, specifically to Angevin England, I had to research that aspect too, and that involved not only the political structure but all the detailed cultural background. I can remember being way too excited over finding a copy of Ewart Oakehott’s work on the archaeology of mediaeval weapons in the library and ignoring my A-level Tudor history homework to read up on 12th century swords!

Basically the more I read up on 12th century life and culture, the more I became interested in the period and the more I wanted to write stories set in that timeframe, so one fed off the other.

Do you think it’s an era that is sometimes overlooked?

I think it’s an era that is perhaps less mined than certain others, but it does have its share of novelists – my good friend Sharon Kay Penman for example. There are the Crowner John mysteries of Bernard Knight, or the novels of Ariana Franklin. And of course Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett. It also has its share of meaty historical incidents – the Anarchy period of the war between Stephen and Matilda, the reign of Henry II and the murder of Thomas Beckett, the Third Crusade. It has towering characters such as the great William Marshal, the loved and loathed Richard the Lionheart, and ditto his brother Prince and then King John. It was a tumultuous period of history, but it’s not quite Tudor territory in terms of saturation, and it does take a dedicated amount of researching. Sometimes people will say it takes less research but that’s not true. It probably takes more to actually understand the period and you have to dig a lot deeper to find what you’re looking for.

You paint a fascinating and complex portrait of your subject, Eleanor of Aquitaine. What attracted you to her and inspired you to choose her as the focus of your latest trilogy?

The Eleanor Vase, currently on display in the Louvre. It was given to Eleanor by her grandfather, William IX of Aquitaine, and she later gave it to her first husband, Louis VII of France as a marriage gift. (Photo credit: John Phillips.)

I was also interested in writing about Eleanor because scholarship is constantly turning up new information. For example, we now know she was more likely to have been 13 years old when she married, not 15 as has been earlier thought, and that puts a whole new slant on the way the character is portrayed. This is someone just out of childhood, a pawn in the power games of men, not a knowing, flirtatious older teenager as she has been so often portrayed. I felt there was a lot to be said that hasn’t been said before, and new, realistic ways of interpreting the material through the medium of fiction.

One of the things you do so well in the series is to bring to life the various conflicts, rivalries and alliances within the royal court. When dealing with so many characters, how do you keep track of all their relationships?

This is going to sound strange, I hope it doesn’t sound big headed – or perhaps I need a big head because the knowledge is all there in my mind! I sometimes have to pick up a reference book to check on a detail but on the whole it’s all there up top. I think it helps that I have been reading about and researching the period 1066-1220 since I was 15 and that’s a long time ago. It does mean that a lot of the history is already there and I can start researching from a strong, multi-layered bedrock. I do write a very detailed synopsis at the beginning of the novel and I can refer to this as a timeline so I guess that’s the skeleton part of the structure.

Mural depicting what is thought to be Henry II and his four sons in the chapel of St Radegonde at Chinon, Indre-et-Loire, France. (Photo credit: John Phillips.)

Some of the historical persons featured in your latest series may be familiar to readers of your earlier novels. Do you ever revise your opinion of particular characters, and does that affect how you portray them in your writing?

Yes. I think we are always learning. Personally, what might have been true of my knowledge 10 years ago may now have changed down to new historical discoveries or increased study and awareness on my part. I wrote a novel called The Champion which is one of my earlier slightly more romantic works where I cut Prince John a little more slack than I would now. But at the same time I probably understand more about John and his personality now and can bring that to bear when writing his character today, so he’d be more nuanced. Sometimes there’s a conundrum when a character has to change hair or eye colour because of new research but if that happens there’s always the author’s note to explain it. I wrote a couple of novels about the Bigod family – The Time of Singing and To Defy A King, where one of my characters, Roger Bigod goes through changes as he ages and life takes its toll on him. I’ve had readers say why is he so different from one novel to the next, but I don’t think he is. It’s just that we grow and change and perhaps become less flexible as we get older. So with a character, if one is being realistic, one has to take into account the changes wrought by time and experience. I go with the truest version I know at the point of writing and make up for discrepancies in the afterword should I need to.

Henry II and Eleanor ruled over a territory that famously stretched from the Scottish Borders to the Pyrenees. How did they maintain their authority over such far-flung lands?

The Summer Queen, the first book in Elizabeth’s Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, is available now in paperback, published by Sphere.

Are there any reference books you can recommend for readers interested in finding out more about Eleanor and her world?

England under the Norman and Angevin Kings • Robert Bartlett

I understand that you are currently writing the final book in the trilogy, The Autumn Throne. What’s next for you?

I’ve discussed the next novels with my publisher, and I can say for definite that William Marshal and his family are once more on the cards. There are gaps in his life that need filling in and I’ve already started research into the background!

*

Many thanks, Elizabeth, for taking the time to talk about your work! The Winter Crown is available now in hardback and as an ebook, published by Sphere. The first book in the trilogy, The Summer Queen, is also available in paperback.

I probably speak for a lot of writers in saying that, as a general rule, we tend not to keep to strict daily routines. Novel-writing is, I think, about as far from a nine-to-five job as it’s possible to get, and the pattern of my working day is very fluid. That isn’t to say that

I probably speak for a lot of writers in saying that, as a general rule, we tend not to keep to strict daily routines. Novel-writing is, I think, about as far from a nine-to-five job as it’s possible to get, and the pattern of my working day is very fluid. That isn’t to say that I only write when inspiration strikes me. A novel is a big project to take on, and if you’re forever waiting until you feel in the right mood before putting pen to paper, it’ll take a very long time to get even a first draft finished.

I do my best to stay disciplined by setting myself a daily target of 1000 words. Sometimes that will take me only a few hours, which means that I have some time to add new material to my website or update my followers on Twitter and Facebook with my latest news. If I’m some way short of that day’s target, though, or even if I’ve reached it but I’m still feeling in the zone, or if I’m feeling the pressure of a rapidly approaching deadline, I’ll often carry on working into the evening.

That said, I do have an absolute cut-off time of 10pm. At that point, if I’m still working, I down tools and shut up shop for the night, regardless of how much or how little I’ve written. Always. Without exception. One of the benefits of being self-employed is that you can define your own working hours, but one of the difficulties comes in setting limits and preventing work from taking over your life. So imposing that cut-off, and sticking to it come what may, is very important for me.

When I first started writing the novel that developed into Sworn Sword, I would spend hours at a time glued to my computer screen, and I’d sometimes get frustrated when I wasn’t as productive as I hoped. With experience, though, I’ve learned that I’m more efficient – and happier – when I write in short bursts of around one to two hours at a time.

In between those bursts I make sure to take decent breaks, in which I’ll grab a coffee, have lunch, go for a walk in the countryside, read a book or watch some TV: anything to help take my mind off writing. That way, when I do get back to my desk, I feel refreshed, and as a result the words flow that much more easily.

Among the many great panel sessions at The Middle Ages in the Modern World at the University of St Andrews was one entitled “Dirt, Dirty Doings and Doing the Dirty”, presented by Susan Aronstein (University of Wyoming), Laurie Finke (Kenyon College), Amy Kaufman (Middle Tennessee State

The 12th-century tower of St Rule (St Regulus), in the grounds of St Andrews Cathedral.

While many of these and other dramatisations dress themselves in the lavish costumes, scene-dressing and CGI that are the hallmarks of the so-called “sexy historical”, the content is often much less glamorous. The main focus of the discussion revolved around the prevalence and degrees of vice, debauchery and violence (including sexual violence) depicted in these programmes, their portrayal of women, and the ways in which they make use of the commonly held belief that the Middle Ages were a period in which life was “nasty, brutish and short”.

Clearly this is a very skewed and limited vision of the period, and yet it seems to be one that the US-based cable networks such as HBO, Showtime and Starz, who commission and in large part fund these series, have hit upon as a means of drawing in viewers. A similar formula can also be found in the treatments afforded to The Tudors and The Borgias. Why is it that this recipe has recently found success, and should we be concerned that the Middle Ages are getting such a bad press?

It should be noted that this new brand of “dirty medievalism” is, by and large, the preserve of the cable channels. Indeed in the UK, the BBC’s dramatic uses of the Middle Ages have tended to be oriented more towards family entertainment, with series such as Merlin and Robin Hood offering a very different depiction of medieval life: one that is gentler and interspersed with humour. Which of the two approaches, if either, presents a better reflection of the medieval reality?

St Andrews Castle (foreground), with West Sands Beach and the North Sea beyond.

Nevertheless, I’d hope that readers of my novels come away with the sense that kinship, duty and love did matter to medieval people, just as they matter to Tancred and his allies, and that there was honour to be found in their world. While treachery, backstabbing, power games and violence abounded, it seems strange to argue that these facets were peculiar to the Middle Ages, or that they were the main distinguishing features of that period. For that reason, as entertaining as these recent TV dramatisations are, there remains for some a nagging sense that, in limiting their vision, they do the Middle Ages a disservice.

Needless to say it was a fascinating discussion – one of many over the course of the conference. Even now, more than a week after coming back, I’m still working my way through and absorbing the various notes I made. I hope to share some more of my findings from my time in St Andrews in the not too distant future!

If you missed it last week, catch up with Part One of my report from “The Middle Ages in the Modern World”.