As 2014 draws to a close, the time has come for me to reveal my favourite books of the year. A few of these are relatively new releases, published within the last twelve months, although some are older.

I’ve divided the list into three sections – fiction, non-fiction and graphical novels – so I hope that there’ll be something for everyone. As you might expect, there’s a strong historical slant: the Middle Ages feature particularly strongly, but my choices also cover Roman Britain, Tudor England and the nineteenth century.

If you’ve enjoyed any of the titles below or would like to share your own favourite books of 2014, feel free to join in the discussion on Twitter (@James Aitcheson) or on Facebook.

Fiction

Alias Grace

Alias Grace

Margaret Atwood

Virago, 560 pp., £8.99

Paperback

Margaret Atwood never fails to impress me with the brilliance of her prose and the scope of her ambition. In a year in which I’ve read no fewer than six of her novels, Alias Grace is the one that has most stood out, and which has left the greatest impression on me.

Based on real events that took place in 1840s Canada, the novel centres upon former housemaid Grace Marks, recently convicted of the murder of her employer and his mistress, and sentenced to life imprisonment. But serious doubts remain regarding her guilt, as the earnest young proto-psychiatist Dr Simon Jordan discovers when he comes to investigate her case.

Told partly through Grace’s eyes and partly from Dr Jordan’s perspective, the novel is an absolute tour de force. Atwood’s prose sparkles throughout, her research into the period is impeccable and her characters are nuanced and fully realised. Alias Grace is one of the most absorbing and complete historical novels I’ve read, and one that almost certainly I will be returning to soon.

Beowulf

Beowulf

Seamus Heaney (trans.)

Faber & Faber, 256 pp., £12.99

Paperback

As a medieval scholar, it shames me to admit that until this year I’d never read Beowulf, perhaps the most famous text written in the Old English language. The exact date of its composition is unknown, although it is unlikely to be less than 1100 years old and perhaps much older, but the tale of the eponymous hero’s struggles against the monster Grendel and, later, against the dragon remains as compelling now as undoubtedly it was to its Anglo-Saxon audience.

The translation, by the late Seamus Heaney, captures the hero’s vitality and the drama of his deeds, and is all the more absorbing and thrilling when it is read aloud. This bilingual edition uniquely features the original Old English text alongside the translation for easy reference.

Also recommended:

- Gentlemen of the Road, a swashbuckling tale of derring-do in the medieval Khazar Empire, by celebrated author Michael Chabon;

- Atwood’s new collection of short stories, Stone Mattress, which was published this summer;

- CJ Sansom’s latest Shardlake novel, Lamentation, set during the final months of Henry VIII’s reign.

Graphic novels

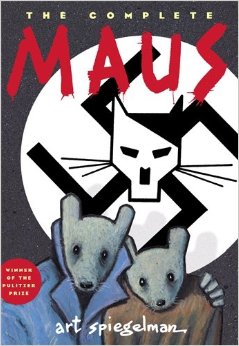

The Complete Maus

The Complete Maus

Art Spiegelman

Penguin, 296 pp., £16.99

Paperback

For the first time my end-of-year list includes a graphic novel, although graphic memoir or biography might be a more appropriate term. Art Spiegelman’s harrowing telling of his father Vladek’s experiences as a survivor of the Holocaust won the Pulitzer Prize when it was published, and deservedly so.

By choosing to depict the subjects of his narrative not as humans but as anthropomorphic animals, Spiegelman takes a bold step, and one that has come in for more than its fair share of criticism. Far from trivialising the events he describes as a cat-and-mouse chase, however, the effect is to allow him to depict subject matter that otherwise might be too horrific for the reader to bear.

Maus is a masterpiece of the genre, a prime example of the power of the graphic novel if ever there was any doubt. Spiegelman’s companion book, MetaMaus, is also well worth reading, for the insights it offers into his early career and how the project came about, his research, the decisions he made in the course of writing the book, and how it affected his relationships not just with his father but with his own children as well.

Non-fiction

Worlds of Arthur

Worlds of Arthur

Guy Halsall

OUP, 384 pp., £10.99

Paperback

The fifth century, which witnessed some of the most momentous events in British history – the end of Roman rule and the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons – is a period shrouded in mystery. In this hugely important study, Guy Halsall demolishes the pseudo-historical case for the existence of King Arthur and examines the historical and archaeological evidence for what took place in that dark age.

Halsall assumes no prior knowledge, although some of the source analysis may seem impenetrable to the general reader, and so some familiarity with the discussions surrounding the period will undoubtedly help. While not all readers will necessarily agree that the evidence supports his specific conclusions, nevertheless Halsall succeeds in opening up the debate on post-Roman Britain and suggesting some new avenues of enquiry. Cogently argued and well illustrated throughout, this is an excellent piece of scholarship – history writing at its best.

The King in the North

The King in the North

Max Adams

Head of Zeus, 464 pp., £9.99

Paperback

The early Anglo-Saxon period is one largely unknown nowadays except to specialists. In this accessible and compelling history, Max Adams rescues from obscurity one of the most powerful rulers of that age: King Oswald of Northumbria (r. 634-42), who according to the historian Bede “brought under his dominion all the nations and provinces of Britain”, and whose reign witnessed the establishment of Christianity and the foundation of the famous monastery at Lindisfarne.

Less a biography of a single man than it is a study of a dynasty, The King in the North depicts a ruthless and volatile world in which Britons fought Anglo-Saxons, pagans fought Christians, and fortunes of entire kingdoms could be overtuned at a single sword’s blow. For a more in-depth discussion, take a look at the fuller review I penned earlier in the year.

Magna Carta: a Very Short Introduction

Magna Carta: a Very Short Introduction

Nicholas Vicent

OUP, 152 pp., £7.99

Paperback

2015 will mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, the great charter between King John and his barons that sought to restrict and regulate royal authority. The document casts a long shadow: even today, it’s often held up as one of the cornerstones of modern democracy, not just in Britain but in the United States as well.

Nicholas Vincent examines the history and context of Magna Carta, including how it was reinterpreted and reframed in the generations following 1215, and asks whether the mythic status that it has acquired over the centuries is justified. Concise and yet comprehensive, it includes a translation of the full text of the original issue. An excellent introduction to the subject.

Also recommended:

- Jared Diamond’s latest book The World Until Yesterday, in which he asks whether as wealthy Westerners we can learn any lessons from traditional, pre-industrial, stateless societies;

- The Middle Ages: a Very Short Introduction, Miri Rubin’s new addition to the long-running series from Oxford University Press, which offers a broad overview of medieval Europe and its society and culture.

- Under Another Sky, part travelogue and part work of history, in which classicist and journalist Charlotte Higgins explores the legacy of the Romans in Britain.

Featured podcast

For more podcasts, visit James's channel on Soundcloud.